|

B.C. Stellar Award, 2016 shortlist

Geoffrey Bilson Award shortlist, 2015 Red Maple Award, 2015 Honour Book CLA Young Adult Book Award, 2015 shortlist Snow Willow Award, 2015 shortlist 2014 Best Book *Starred* Choice by Canadian Children's Book Centre |

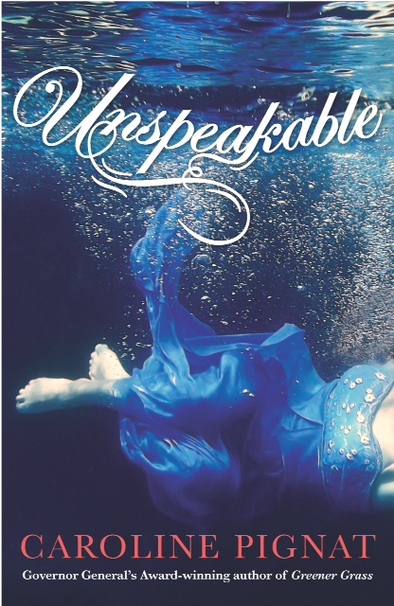

A heart-wrenching, beautifully written account of a maritime tragedy that rivals the Titanic disaster. Working as a stewardess aboard the Empress of Ireland allows Ellie Ryan to forget about why she has been banished from the family home, why her great aunt ultimately had to find her this job. On her second voyage, Ellie finds herself drawn to the solitary fire stoker who stands by the ship's rail late at night, often writing in a journal.

Jim. Ellie finds it hard to think of him now, after that awful night. She tries to tell herself that he survived, but it's hard to believe when so many didn't.

So when Wyatt Steele, journalist for The New York Times shows up at her door in Liverpool, England, and asks for her story, Ellie refuses. But when he shows her Jim's journal, she jumps at the chance to be able to read it herself, to find some clue of the man she had fallen in love with, perhaps a clue to what happened to him. There's only one catch: she will have to tell her story to Steele and he'll "pay" her by giving her the journal. One page at a time.

Guided by Steele, Ellie slowly opens up. But more lies at the heart of her story than even Ellie knows, and as she spends more time with Steele and Jim's journal, she discovers what was once unspeakable -- for both her and Jim.

Based on the true story of the sinking of the RMS Empress of Ireland in May 1914, a disaster that lost more passengers' lives than Titanic, Unspeakable will be published in time to mark the 100th anniversary of this tragedy.

April 2014, Penguin Canada

historical fiction, 12+

Jim. Ellie finds it hard to think of him now, after that awful night. She tries to tell herself that he survived, but it's hard to believe when so many didn't.

So when Wyatt Steele, journalist for The New York Times shows up at her door in Liverpool, England, and asks for her story, Ellie refuses. But when he shows her Jim's journal, she jumps at the chance to be able to read it herself, to find some clue of the man she had fallen in love with, perhaps a clue to what happened to him. There's only one catch: she will have to tell her story to Steele and he'll "pay" her by giving her the journal. One page at a time.

Guided by Steele, Ellie slowly opens up. But more lies at the heart of her story than even Ellie knows, and as she spends more time with Steele and Jim's journal, she discovers what was once unspeakable -- for both her and Jim.

Based on the true story of the sinking of the RMS Empress of Ireland in May 1914, a disaster that lost more passengers' lives than Titanic, Unspeakable will be published in time to mark the 100th anniversary of this tragedy.

April 2014, Penguin Canada

historical fiction, 12+

Excerpt from Unspeakable.

I started at the hospital and then the nearby homes. All that afternoon, I ran from house to house, calling their names until I was hoarse. Monique came with me, speaking fast French to neighbours who looked at me with sad eyes and shook their heads. And when my search had led us road after road, house after house down to the thick planked quayside shed, I knew I’d looked everywhere. Everywhere but there.

And I just couldn’t go in. I couldn’t.

The door opened and two men exited. The tall man with the dark hair glanced briefly at Monique before his dark eyes rested on me. He wasn’t from around here. Even before he spoke, before I heard his American accent, I knew. His clothes were too smooth and tailored. But more than that, his gaze held no pity. He was no farmer. No victim. He wasn’t here to offer or seek help. He smiled at me. Any other time and place, I might have thought this twenty-something young man handsome, might have longed for his attention, but here and now, his intensity unnerved me.

“Were you a passenger, mademoiselle?” The shorter of the two asked.

“Stewardess,” I mumbled, wondering if they might be CPR officials.

“Mind if I take your picture,” he said raising the camera to his eye, “for the Montreal Gazette?”

“Actually,” I said, raising my hand to cover the lens. “I do mind.”

“Wyatt Steele, New York Times,” the taller held out his hand. I didn’t take it. “The world wants to hear your story, Miss...” He fished for my name and once again came up empty. But he wouldn’t be deterred. He flipped open his notebook. “Can I ask you a few questions?”

I eyed the door, considered what was behind it. “Let me ask you something. What business do you men have in there?”

“Memorial postcard,” the short man said.

“What?” I looked at him in disbelief. “You actually took a picture of the dead… for apostcard?” The rage surged from a place deep inside me. “Did you ask them if they minded?”

“Just doing my job,” he shrugged. “The public have a right to know.”

“And what about the deceased?” I snapped, pointing at the shed. “Do they not have any rights? To dignity? To privacy? To respect?”

“They deserve to have their story told,” Steele answered. “By someone who was there, by someone who survived.” He rested his hand on my shoulder. “Don’t you think you owe them that?”

“Get away from me,” I shirked away, “you -- you vultures!”

Monique stepped in and in no uncertain tone put the men in their place. I don’t know if Steele spoke French, but he got the message just the same. She took me to her home then, murmuring her words of comfort, tucking me under her wing. I let her fuss. Let her stoke up a roaring fire and wrap me in a thick quilt. Let her make a cup of tea I wouldn’t drink and back bacon sandwiches I wouldn’t eat.

Maybe at least one of us would feel like she was doing something.

They thought I was sleeping in the guest room — as if I would ever sleep soundly again. I heard Monique puttering about making Claude’s tea, the spoon clinking on his cup, the knife scraping his sandwich in two. And the halting sound of his voice. This tough old farmer, reduced to tears as he’d told his wife what he’d done that day. What he’d help carry from the ship decks to the shed. I didn’t understand a word of French, but I knew exactly what he said.

For now we all spoke grief.

I started at the hospital and then the nearby homes. All that afternoon, I ran from house to house, calling their names until I was hoarse. Monique came with me, speaking fast French to neighbours who looked at me with sad eyes and shook their heads. And when my search had led us road after road, house after house down to the thick planked quayside shed, I knew I’d looked everywhere. Everywhere but there.

And I just couldn’t go in. I couldn’t.

The door opened and two men exited. The tall man with the dark hair glanced briefly at Monique before his dark eyes rested on me. He wasn’t from around here. Even before he spoke, before I heard his American accent, I knew. His clothes were too smooth and tailored. But more than that, his gaze held no pity. He was no farmer. No victim. He wasn’t here to offer or seek help. He smiled at me. Any other time and place, I might have thought this twenty-something young man handsome, might have longed for his attention, but here and now, his intensity unnerved me.

“Were you a passenger, mademoiselle?” The shorter of the two asked.

“Stewardess,” I mumbled, wondering if they might be CPR officials.

“Mind if I take your picture,” he said raising the camera to his eye, “for the Montreal Gazette?”

“Actually,” I said, raising my hand to cover the lens. “I do mind.”

“Wyatt Steele, New York Times,” the taller held out his hand. I didn’t take it. “The world wants to hear your story, Miss...” He fished for my name and once again came up empty. But he wouldn’t be deterred. He flipped open his notebook. “Can I ask you a few questions?”

I eyed the door, considered what was behind it. “Let me ask you something. What business do you men have in there?”

“Memorial postcard,” the short man said.

“What?” I looked at him in disbelief. “You actually took a picture of the dead… for apostcard?” The rage surged from a place deep inside me. “Did you ask them if they minded?”

“Just doing my job,” he shrugged. “The public have a right to know.”

“And what about the deceased?” I snapped, pointing at the shed. “Do they not have any rights? To dignity? To privacy? To respect?”

“They deserve to have their story told,” Steele answered. “By someone who was there, by someone who survived.” He rested his hand on my shoulder. “Don’t you think you owe them that?”

“Get away from me,” I shirked away, “you -- you vultures!”

Monique stepped in and in no uncertain tone put the men in their place. I don’t know if Steele spoke French, but he got the message just the same. She took me to her home then, murmuring her words of comfort, tucking me under her wing. I let her fuss. Let her stoke up a roaring fire and wrap me in a thick quilt. Let her make a cup of tea I wouldn’t drink and back bacon sandwiches I wouldn’t eat.

Maybe at least one of us would feel like she was doing something.

They thought I was sleeping in the guest room — as if I would ever sleep soundly again. I heard Monique puttering about making Claude’s tea, the spoon clinking on his cup, the knife scraping his sandwich in two. And the halting sound of his voice. This tough old farmer, reduced to tears as he’d told his wife what he’d done that day. What he’d help carry from the ship decks to the shed. I didn’t understand a word of French, but I knew exactly what he said.

For now we all spoke grief.